Long Warf

From Long Wharf’s timbers to Faneuil Hall,

A whisper turned to the roar of all.

Posts on this site may contain copyrighted material, including but not limited to music clips, song lyrics, and images, the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. Such material is made available for purposes such as criticism, commentary, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, education, or research, in accordance with the principles of fair use under Section 107 of the U.S. Copyright Act.

Long Warf

[Instrumental Intro]

[Verse 1]

Down by the water where the ships all sway,

Timbers groan and gulls give way,

Dreams are traded in a sea-born gray,

At the end of the Long Wharf day.

Barrels roll with rum and tea,

Chains of faith and liberty,

Merchants count their destiny,

On the tide of a restless sea.

[Chorus]

Raise your voice, let the harbor ring,

For freedom’s bell is a fragile thing,

From Long Wharf’s timbers to Faneuil Hall,

A whisper turned to the roar of all.

[Verse 2]

Hancock’s ships with their silken sails,

Bring gold and risk and rebel tales,

Adams speaks where the courage fails,

And the crown begins to pale.

Voices echo on cobblestoned dreams,

“Taxation’s chains will tear at seams,”

The harbor knows what liberty means,

When the tea meets the moonlit sea.

[Chorus]

Raise your voice, let the harbor ring,

For freedom’s bell is a fragile thing,

From Long Wharf’s timbers to Faneuil Hall,

A whisper turned to the roar of all.

[Bridge]

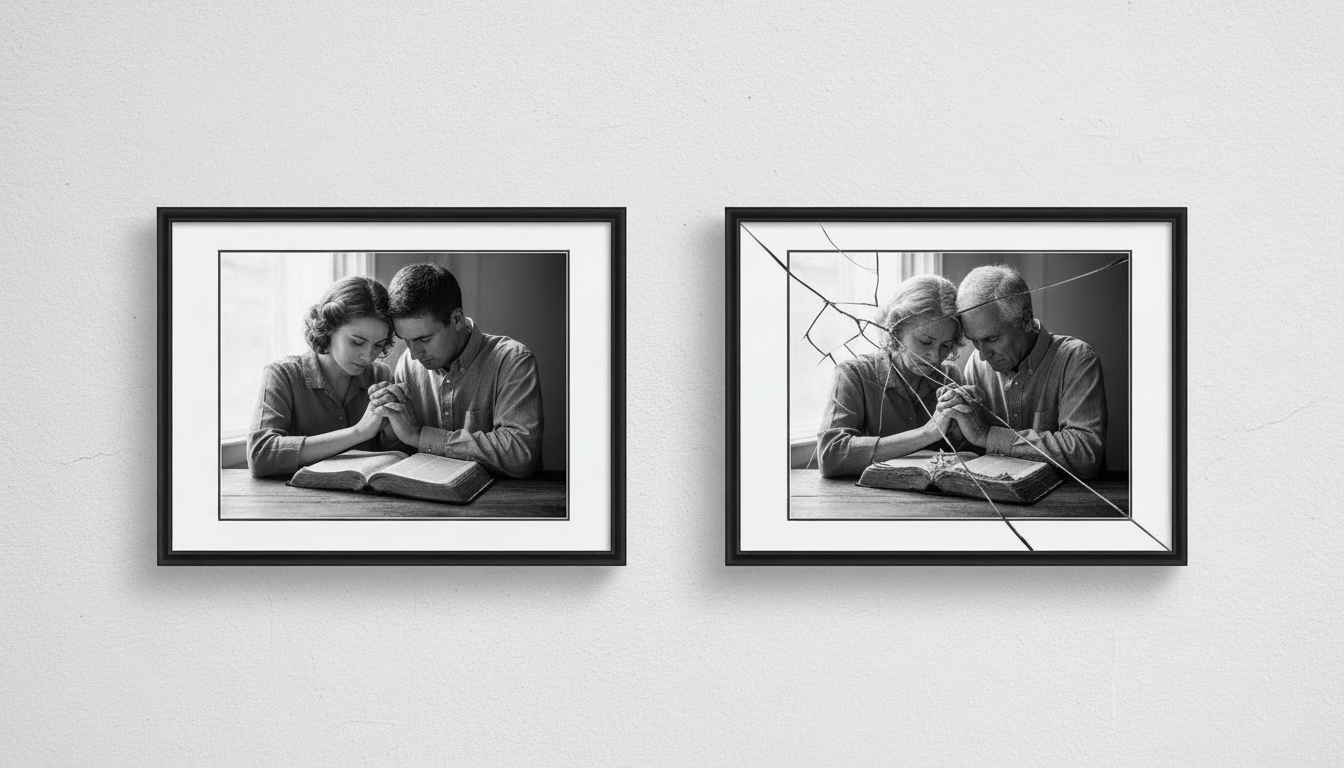

Candles burn where the truth was born,

Through winter’s bite and summer’s morn,

Every oath, each word of scorn,

Forged a country, brave and worn.

[Verse 3]

Now the tourists walk where blood once ran,

And history’s ghosts still take their stand,

A dock, a hall, and a band of men,

Who spoke and dreamed again.

[Final Chorus]

Raise your voice, let the harbor sing,

Of rebels bold and the hope they bring,

From Long Wharf’s planks to the liberty call,

The heart of a people, one and all.

[Outro (Spoken/Softly Sung)]

By the water, under twilight’s flame,

Freedom whispered every name…

At Long Wharf… it all began.

This is original work is produced by AK Darvinson with a combination of observation, critical thinking, insight, heart, compassion, passion, creativity, and technology. All rights are reserved. Free sharing is encouraged. Commercial use via license only.

Boston’s Long Wharf and Faneuil Hall: A Nexus of American Commerce and Revolution

I. Origins of Long Wharf

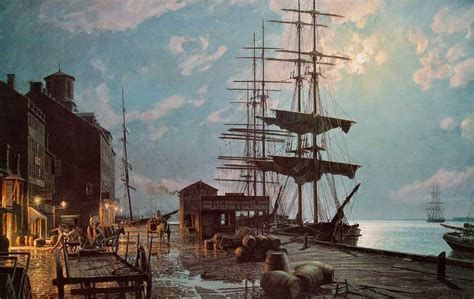

Constructed between 1710 and 1721, Boston’s Long Wharf was one of the most significant maritime structures in colonial America. Extending nearly half a mile into Boston Harbor, it was a feat of early engineering—built on piles of timber, stone, and earth, designed to accommodate the largest merchant ships of the day. The wharf quickly became the economic heart of Boston, connecting the young colony to global trade networks with the West Indies, Europe, and Africa. Its bustling warehouses, markets, and taverns exemplified New England’s rise as a maritime power.

By the mid-18th century, Long Wharf had evolved into a symbol of both prosperity and protest. Imported goods such as tea, molasses, and textiles flowed through its docks, enriching Boston merchants while binding the city to the British mercantile system that would soon become a source of rebellion.

II. Faneuil Hall: The Marketplace and the “Cradle of Liberty”

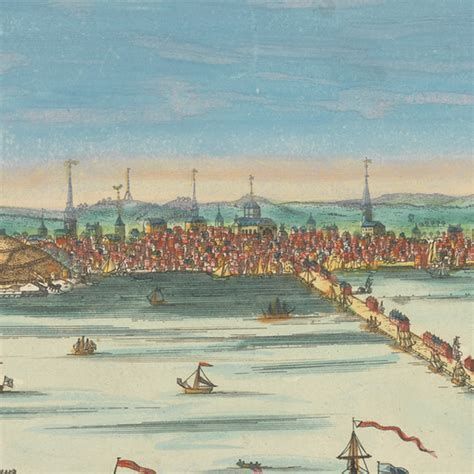

Just a short walk inland from Long Wharf stands Faneuil Hall, built in 1742 by wealthy merchant Peter Faneuil as a public market and meeting hall. Though a commercial hub, it quickly acquired a political identity. The upstairs meeting room became a gathering place for public debate, where merchants, politicians, and citizens alike voiced grievances against the British Crown.

Faneuil Hall became the epicenter of revolutionary discourse in Boston. Meetings held here protested the Sugar Act, the Stamp Act, and the Townshend Acts. Figures such as Samuel Adams, James Otis Jr., and John Hancock regularly took the podium, articulating the ideals of self-governance and liberty that would define the coming revolution. So powerful were the debates held here that it earned its lasting nickname: “The Cradle of Liberty.”

III. The People of the Wharf and Hall

A host of notable figures shaped—and were shaped by—this tight geography of commerce and politics:

Samuel Adams: A key revolutionary organizer, Adams used meetings at Faneuil Hall to rally resistance against British taxation. He also helped organize the Boston Tea Party, an act directly connected to the trade dynamics of Long Wharf.

John Hancock: One of Boston’s wealthiest merchants, Hancock’s ships docked regularly at Long Wharf, and he was accused by British authorities of smuggling to evade imperial taxes. His business and political interests converged at this site, where he became a symbol of colonial defiance.

Paul Revere: The silversmith and patriot who would make his famous midnight ride was a familiar face around these parts, using the area’s network of taverns and meeting halls to exchange information and distribute revolutionary pamphlets.

James Otis Jr.: Known for arguing that “Taxation without representation is tyranny,” Otis’s fiery speeches at Faneuil Hall helped give intellectual weight to the independence movement.

Even Benjamin Franklin, as a young printer’s apprentice in the early 18th century, walked these same cobblestones before leaving for Philadelphia.

IV. A Stage for Revolution

The proximity of Long Wharf and Faneuil Hall created a continuous corridor where economic tension fermented into political change. The same ships that brought British goods to the colonies also carried the policies that incited protest. When the British imposed taxes on imports, Boston’s merchants and craftspeople—whose livelihoods depended on maritime trade—reacted immediately. The Non-Importation Agreements and boycotts were first discussed and organized around Faneuil Hall and its neighboring taverns.

It was from Long Wharf that British troops disembarked during the occupation of Boston in 1768, escalating tensions that would erupt into the Boston Massacre just a few years later. And it was from this same harbor, only steps from Faneuil Hall, that colonists boarded ships during the Boston Tea Party in 1773, dumping British tea into the water as an act of defiance that reverberated around the world.

V. Legacy and Impact on American History

Together, Long Wharf and Faneuil Hall represent the merging of commerce and conscience in America’s birth story. They were not merely physical spaces but arenas of transformation—where ordinary Bostonians became active participants in shaping a democracy. In the developing American identity, these landmarks stood for self-determination, civic engagement, and the rejection of imperial control.

In the centuries since, both sites have remained vital to the American narrative:

Faneuil Hall continues to serve as a public meeting place, still echoing the civic values of debate and participation.

Long Wharf today is both a historic site and modern attraction, preserving traces of its colonial symmetry while connecting Boston’s past and present as a maritime city.

Conclusion

From the bustle of ships docking at Long Wharf to the fervent speeches that shook Faneuil Hall, this part of Boston encapsulates the emergence of America’s revolutionary spirit. Here, commerce intertwined with politics, and everyday citizens took up the mantle of history. The stories that began along the waterfront and echoed through Faneuil Hall did more than shape a city—they helped define a nation.